Garrett Phelan has seen some remarkable things

It is inconceivable that someone with hearing could imagine what it is to live in sign language, to experience self-awareness in the configurations of hands and the movement of fingers; and likewise impossible to understand how it might be to think in utter silence. Creatures without the same auditory apparatus as ours, for instance snakes, insects or fish, are commonly regarded as deaf. Animals with limited vision, moles and bats, we characterize as blind.

The ways animals have evolved to negotiate the world is fascinating. Their strangeness is something that collectively we marvel at, appreciate and also disregard. At the heart of this ability to both take astonishing variety for granted and to wonder at it, is the powerful, intuitive sense of our normality. We may intellectually acknowledge that we are generally bi-pedal, binocular, four-limbed, upright animals with a limited sense of smell and opposable thumbs, and so forth; but we move through the world, mostly taking our specific configuration of sense and physical abilities as a given.

When describing the unimaginatively named blind mole rats as blind, it distinguishes them, not just from other mole rats, partially sighted, naked or furred, but also from us. Yet, it seems peculiar to refer to a creature that is without one or another (functioning) sense organs as lacking in that sense. Humans, considered from the perspective of other animals, are terribly deficient. Amongst other things we are tailless, ‘naturally’ flightless, dry-nosed, featherless; we lack pedipalps, dewlaps and cannot lay eggs or jump very high. I was on a plane travelling from North America to Ireland listening to the sound works of artist Garrett Phelan, the accounts of his various extraordinary encounters with birds, when the gravity and the extent of our multiple handicaps dawned on me. At least, I thought, we have mastered the art, the physics, of flying. That is something.

There are still people who fear to fly. Even in spite of its relative statistical safety as a mode of transport there are many more who feel their stomach knot during take off, turbulence or landing. Numerous other less remarkable fears plague us. Some are reasonable things to dread (even if unlikely to occur in the near future): fears of debilitating accident, of fatal illness, loss or unsought change. A dismaying question in this vein is if we were to be without sight or hearing, which sense would we sacrifice? It is a talking point that spins around the sense we have of ourselves, our resilience, our capacity to cope, to relate to and endure a newly strange life. A world in which we may still think in colour and light, but will not see it; in which we might know our loved ones voices, but will never again hear them.

I lack one faculty commonly found in many animals, Homo sapiens included, that is, a sense of direction. I am not comparing this to the aforementioned blindness or deafness, but having no ability to intuitively locate oneself in even a familiar environment greatly affects the way one can engage with the world. And if describing myself to a bird though chiefly I would be conscious of my regrettable tailless-ness, (there are a lot more birds that are flightless than without a tail), I would have to declare, to this imaginary bird auditor, my profound inability to find my way.

My deep-seated fear of getting lost is not reasonable. Given that I do not climb mountains or visit war-zones what terrible consequences beyond inconvenience or delay might befall someone who is somewhat lost? Yet an accidental or unavoidable deviation from a route carefully learned can still be bizarrely stressful; gut and brain conspire to whip up a frenzy of suburban anxiety wherein for the want of a nail a kingdom is forfeited. And so, in the past, in the midst of being lost I tried to stay calm and console myself with the tantalizing possibility that I might see or hear something new or unexpected; perhaps I would think, there might be a story in this.

Nowadays, I take out my phone.

Scientists have studied the small, reptilian brains of birds’ attempting to uncover what enables them to navigate vast distances, and/or to return to the same small place with unerring precision year in and out. Casting a quick eye at accounts of such research I see that certain key words recur - the Earth’s magnetic field and the positing of birds’ beaks, eyes, the inner ear, etcetera, as the seat of their mysterious power. There is as yet, however, no consensus on how birds find their way.

“Other pioneers of flight were focused on the question of power. The Wrights were fascinated by birds, and learned a lot from their study of them. One of Wilbur’s crucial insights was that flying, like cycling, was a question of balance. He saw that bird flight was all about equilibrium: about the bird’s keeping itself in the air with the maximum efficiency and minimum effort.” John Lanchester, London Review of Books, Vol. 13. Issue 17: 2015.

Flight is arguably the skill that most taxed and stimulated humans to overcome their physical delimitations. We can climb, swim, travel quickly, build and dig. But only very recently, thanks in part to the close study of the class Aves, and extraordinary mechanical ingenuity, have we learnt to fly. The invention of plane travel evidences the attainment of a capacity that for eons seemed unachievable. Reviewing a biography of the Wright Brothers by David McCullough, John Lanchester recounted a peculiar anecdote pertaining to their early career: not one reporter showed up to cover the first publicly staged and afore-advertised demonstration of human flight in a field in Dayton, Ohio. However, a local bee expert witnessed the event and wrote a short piece in his own journal ‘Gleaning Bee Culture’. He forwarded the article to Scientific American. They responded a year later with the remarkable assertion that the flights could not have happened because if such an extraordinary event were to take place a reporter would have been there to bear witness.

No intrepid journalist, no event.

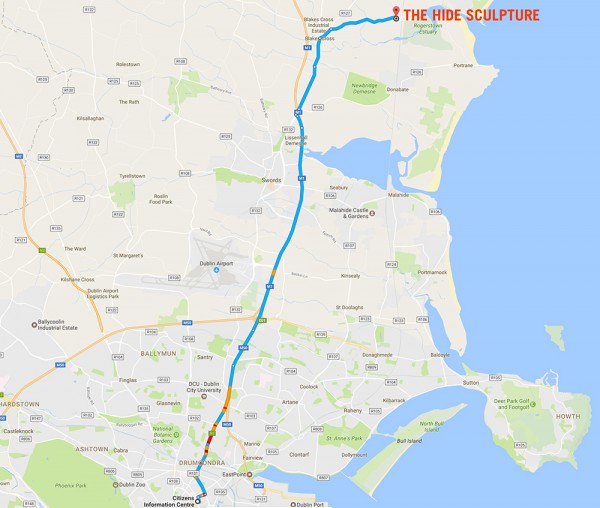

According to his sound works titled ‘Roding Glowing Woodcock on Reconnaissance’, 2008 and ‘Electro Skylarks’, 2006, Garrett Phelan has seen some remarkable things: woodcocks glowing at dusk with a phosphorescent pale blue light. In another instance, first a lone and then an entire exultation of skylarks flying in an unusual pattern, gathering and generating remarkable electrical effects off the Shelly Banks of Dublin’s Irishtown Nature Reserve. Given that he is not an ornithologist, nor a reporter but an artist, his observations may seem incredible. However as set forth in his narrated records of the events he is usually not alone. At times he addresses a silent companion, at others he has serendipitously encountered passers-by who have also observed these otherwise undocumented phenomenon. At least one witness responded negatively to the strange sight, taking off on a bicycle. Disbelief is often easier to compass mentally than accepting that the familiar world can become in an instant utterly, bewilderingly, fearfully new.

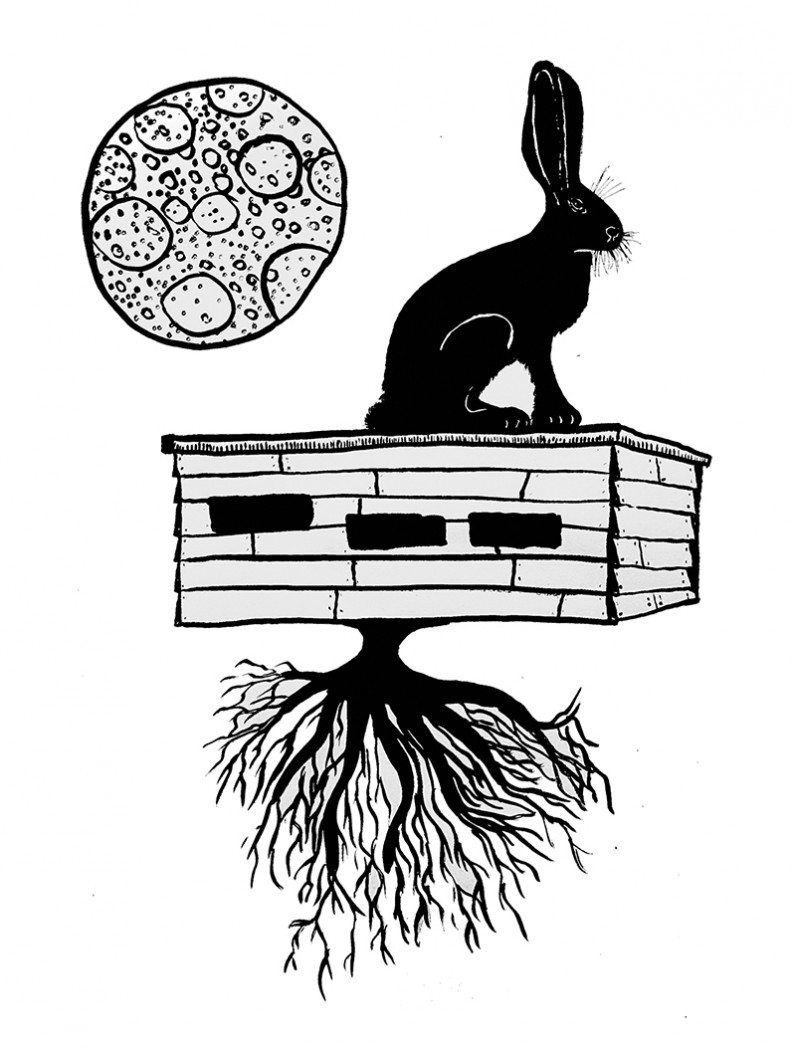

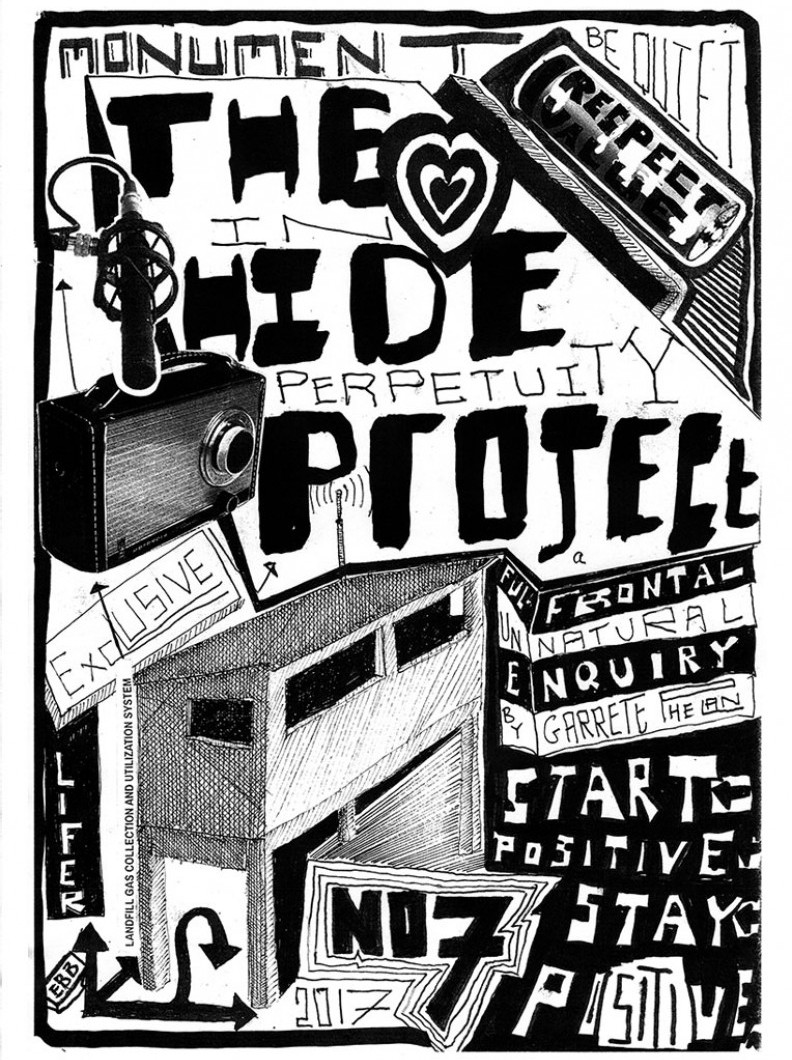

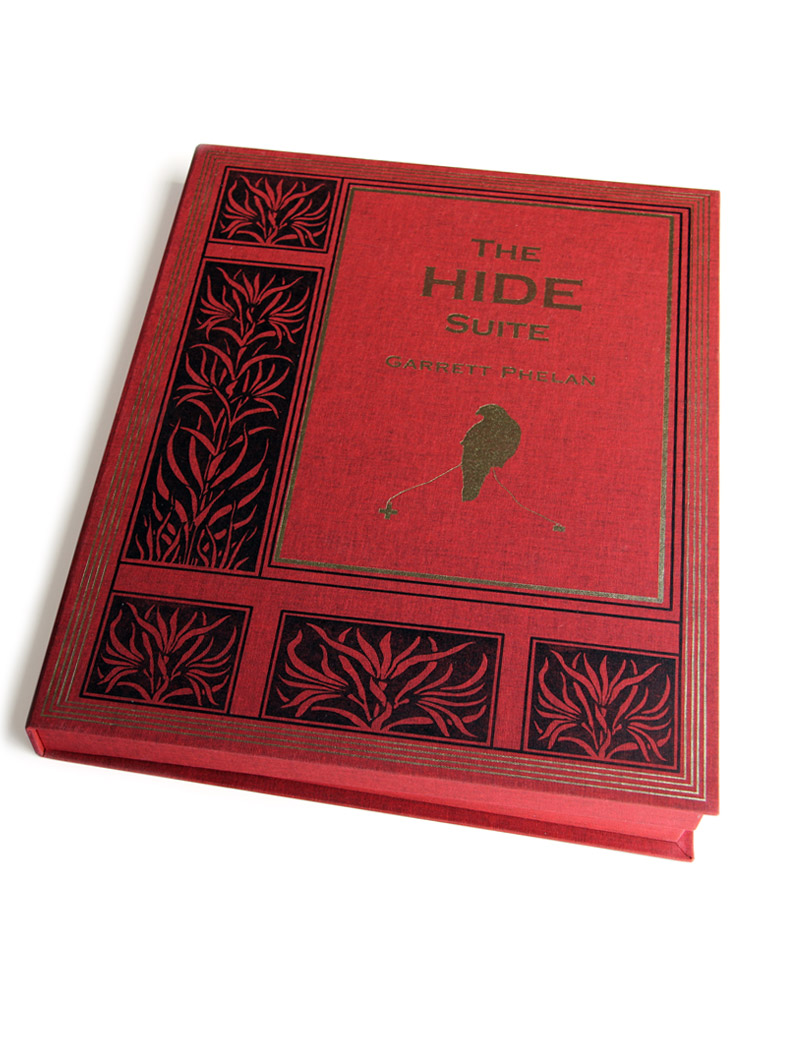

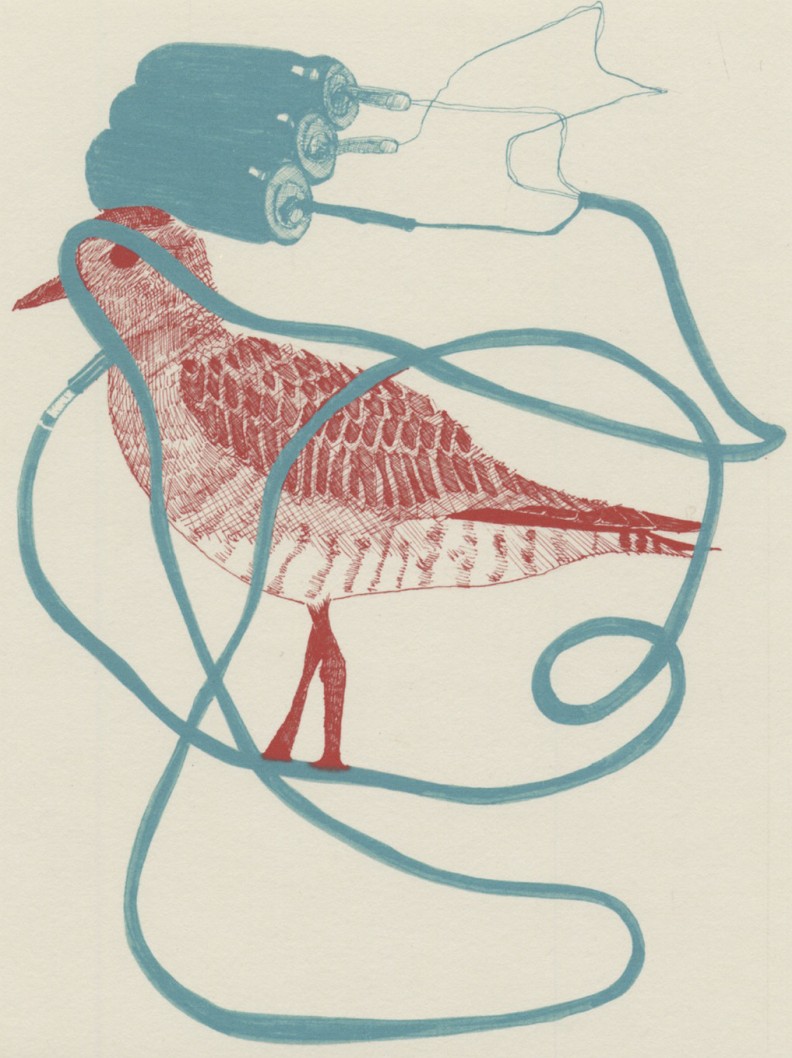

We know there are birds that can use tools, and some that can distinguish humans who are a threat from those who are friendly. The implication of Phelan’s ‘THE HIDE SUITE’, 2015, is that birds may be able, or perhaps will be employed (involuntarily or otherwise) to harness their relationship with the magnetic fields of the planet by augmenting their bodies with batteries. This seems, all things considered, somehow reasonable. After all humans have learnt to fly. If, like us, birds could want what they do not easily have the capacity to achieve, what might they wish for? Which of their senses might they aspire to improve? What deficiencies might they perceive in themselves? That is part of the mystery at the heart of Phelan’s recent series of prints.

We do not know what, or how, the birds, as a class or as families or as individuals might think. But, again to speculate from the imagined point of view of the bird, humans are map-less, beak and bill-less, featherless, tail-less and incapable of sensing the earth’s magnetic field. But latterly, augmented with a smart phone or satnav there is a GPS safety net into which we repeatedly cast ourselves. “Am I almost there?” What GPS saves us from is not simply getting lost, but the uncertainty of not knowing whether or not we are even travelling in the right direction.

I wish we could know if birds can feel unsure. (I suspect, with my human shaped mind, that uncertainty of some kind or another is the condition of being animal.) Part of our human lack of surety primes us to fear other animals. It is not uncommon to find people who have a phobia of birds. To me birds, like spiders, sea cucumbers, or hate-filled Christians, are weird, not necessarily frightening, but truly other. They belong to that category of creature so utterly different as to be un-relatable. The strangeness of birds, as Phelan’s works often intimate, is too broad to fathom or easily describe. Even when domesticated they seem potentially savage. Fierce or placid they have an appearance of purpose that can be unnerving. Their beaks are the shivs, spoons, pliers, hammers, spears and stilettos of the animal kingdom. As Daphne Du Maurier quite rightly registered in her short story ‘The Birds’, if they ever turn on us we do not stand a chance.

In Act One of the Tom Stoppard play ‘Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead’ Guildenstern observes:

“A man breaking his journey between one place and another at a third place of no name, character, population or significance, sees a unicorn cross his path and disappear. That in itself is startling, but there are precedents for mystical encounters of various kinds, or to be less extreme, a choice of persuasions to put it down to fancy; until--"My God," says a second man, "I must be dreaming, I thought I saw a unicorn." At which point, a dimension is added that makes the experience as alarming as it will ever be. A third witness, you understand, adds no further dimension but only spreads it thinner, and a fourth thinner still, and the more witnesses there are the thinner it gets and the more reasonable it becomes until it is as thin as reality, the name we give to the common experience....”

The reality Garrett Phelan presents us with is anything but thin; his ornithological works may be so pioneering that few would give credence to his tales. But something as minor as the absence of journalists does not mean we should doubt the acuity of his senses. The truths that he documents in his works are rich, they are full and feel prescient. When it comes to descriptions of the world too close a correspondence with reality can be profoundly unrevealing; and it can be unrewarding to attend to a story reiterating precisely what we already know. Phelan’s works have a magnitude and scope that is hard to describe. Even when his efforts or investigations peter out or fail to arrive at the anticipated conclusions, such as the events recounted in ‘Hide’, 2007 and ‘A VOODOO FREE PHENOMENON - Film’ 2014, we see an investigatory prowess at work that reveals the sorts of truths that feel real. Love can heal. And forces, physical, sonic, optical, mental and sensual can resonate through space and through time and affect and connect us all.

Phelan might see things you would not believe but maybe time will reveal him to be something of a seer. It isn’t second sight at work but a powerful, synthesizing intelligence that perceives the forces of the universe as a stage, an infinitely large stage, where love, instinct, reason and the desire to make sense of it all coalesce to produce our lived experience. A reality wherein we understand that our knowledge of animals, of birds, of historical powers, of electromagnetism, electric effects, radio waves and the power of the human mind to observe, sense and collate is both tremendous and circumscribed. Most crucially of all Phelan shows us a world where our understanding has been subjected to and continues to undergo momentous change. Everything is evolving.

Perhaps, if like Phelan, we see the potential in everything to connect, by loving birds, observing them, enriching their habitats, and encouraging them to develop technologies that may see them flourish, we could someday learn that the world is experienced on sensory levels as yet profoundly unfathomable to us. And though we may never experience it, we could discover that it is possible to never feel lost, or to think in air-currents and have an electro-magnetic intellect tuned to the turning of the world.

Isabel Nolan, 2016

Download text